“I believe that the body knows something that intellectually, I can’t access.”

—Patty Seyburn

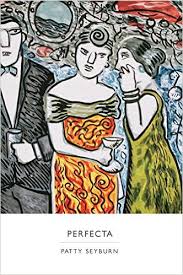

Patty Seyburn has published three volumes of poetry. Her third book, Hilarity, won the Green Rose Prize given by New Issues Press (Western Michigan University, 2009). Her two previous books of poems are Mechanical Cluster (Ohio State University Press, 2002) and Diasporadic (Helicon Nine Editions, 1998) which won the 1997 Marianne Moore Poetry Prize and the American Library Association’s Notable Book Award for 2000. Her poems have appeared in numerous journals including The Paris Review, Poetry, New England Review, Field, Slate, Crazyhorse, Cutbank, Quarterly West, Bellingham Review, Boston Review, Cimarron Review, Third Coast, and Western Humanities Review. She won a 2011 Pushcart Prize for her poem “The Case for Free Will,” published in Arroyo Literary Review. She holds an MFA in Poetry from University of California, Irvine, and a Ph.D. in Poetry and Literature from the University of Houston. She is an Associate Professor at California State University, Long Beach. Patty Seyburn’s official website: click here.

[Note: bolded text is my emphasis; these passages really spoke to me {m}]

♦

Meredith: I was trained as a therapist and as a result was trained to strike a delicate balance of letting the client guide the session but also encouraging growth and change. There are, however, times when the therapist, in order to help the client move forward (or deeper), must raise issues to keep the process from stagnating. How do you see this playing out for the creator/writer? For you?

PATTY: My first instinct is to question whether the poem is the therapist or the client…

Frost wrote, “Like a piece of ice on a hot stove, the poem must ride on its own melting.” For a while, early in the poem’s life, it rides on its own melting. And then, it stops, and it’s not always evident what is next. Is it done? Possibly. To stay with Frost – is it a fork in the road, “two roads diverged”? Probably. At that point, I try to look at what the poem wants to say. Some people will tell you that they never do that, that in the course of writing, they never think about ideas, like William Carlos Williams: “No ideas but in things.” I grant that the consideration of meaning (that’s an obscenity for some poets) must come later in the process, or you end up guiding th e poem to “say something,” though it’s probably more like “say anything.” I don’t really want my poems to say anything. They represent me out in the world. They are often not autobiographical in terms of narrative details, but they certainly speak to how I think. They don’t have to say whatever is “the right thing” (not that I know), but they can’t lie.

e poem to “say something,” though it’s probably more like “say anything.” I don’t really want my poems to say anything. They represent me out in the world. They are often not autobiographical in terms of narrative details, but they certainly speak to how I think. They don’t have to say whatever is “the right thing” (not that I know), but they can’t lie.

Of course, the poem can’t say: here’s what I want to talk about, but I don’t know how, or, are you still mad at your mother? In a way, however, it does just that, if you ask nicely. The way to do so, for me, is by scrutinizing each line, and trusting that when the language merits attention in the mouth and body, the content has something to offer. I trust the ear. I trust that catch in the stomach when I hear a C major 7th chord (think of the song, “Misty”). ”). I believe that the body knows something that intellectually, I can’t access. When I manage to craft a strong line, then I have to take seriously what it says, though I’m not always happy with that, because it reveals something about me to myself that I may not know (and like), or may not know (and not like), or may know (and not want to admit). I think a good therapist does not let you lie to her or yourself – or that’s the goal. When you write a poem you are proud of, it does the same: it reveals you to yourself, and also, to others. Though, ultimately, it’s a less private affair than therapy, if you publish.I beli

♦

Meredith: Homeostasis is a concept I learned on my first day of graduate school. It means the desire to revert back to the familiar, for things to remain the same. As a writer, how do you remedy this type of stagnation which can thwart creativity? Or, do you believe there’s a time for it?

PATTY: If the familiar is defined as a poem that I already know how to write, which is to say, I have already written, then I have limited interest in returning to that technique or strategy. What thwarts the seeming ease of this response is that, to some degree, once I have written a poem, I no long know how to write it. Each poem makes different demands, and just because two poems may seem to share a form, or a rhetorical approach, does not mean that they have anything else in common. I can read Phil Levine’s What Work Is (the collection, and the poem, itself), over and over, and though many of the poems are visually similar, their internal moves continue to surprise me. As well, once I have a little more distance from a poem, I truly don’t know how I did what I did.

I’ll admit, I have a few poems that I wrote recently and am wondering how I could employ that strategy again, because I like these poems and think their approach to the subjects worked. If I go back farther, for example, to my third book, w

ritten from about 2001-2005, I have no idea how to write these weird little semi-surrealist, image-driven sort-of lyrics. If I go back to my first book and look at personae poems written in the voices of unnamed or unsung women from the Hebrew bible, I think, wow, how did you do that? Then I was working with Richard Howard, one of the great poets/critics/translators of the 20th-21st century, and he championed those poems, which, no doubt, inspired me. I truly have no idea how to write those, anymore. Not a clue. So, for me, while the familiar has no theoretical attraction, in practical terms, I don’t even know how to get back there. “You can’t go home again,” wrote Thomas Wolfe. One’s poems each provide a temporary home, and you can’t go back to any of them. Sigh. A lot of lonely wandering with clouds for company.

♦

Meredith: I once heard Ira Glass, host of This American Life, say: “Keep following the thread where instinct takes you. Force yourself to wait things out.” Does your writing require a lot of waiting?

PATTY: Whereas I value patience in the writing of poems, and in life, as well, I am less interested in waiting for “the muse,” and I try to teach my students not to value that idea. “Instinct” is a tough word, in relation to poems. Actually, I don’t really understand it, in relation to poems. I trust my instincts (sometimes) about people, about situations. When I write a poem, it’s not instinct at play. It’s language, which contains music, idea and image. It’s not a guessing game. I don’t “wait” for something to happen, in order to write a poem. I observe the world; I take in, ingest, inhale as much as possible, and I trust that what I take in has some resonance, in on the same frequency as something else that matters to me. I don’t wait for inspiration, or for the mood. Having a family and a job precludes what could be interpreted as the passivity of waiting. I think the idea of “forcing – waiting” is an interesting dichotomy. When I have time to write, I write. If I can’t write, I read. Sometimes I’ll read first. I imagine he’d say I was being ornery, but I’ll admit, I cherish urgency more than patience. I don’t do much yoga.

♦

Meredith: How do you not hold on so tight to a piece of writing that isn’t working (that you wish would work) and let go so you might discover what will work?

PATTY: I have had to school myself in editorial brutality and trusting in the editing wisdom that comes with time. Generally, when I revise a poem into oblivion (as I did just the other day), and it’s taken up a great deal of my time (of which I do not have much, being a mom and a professor at Cal State Long Beach), I know that all I can do is put it away, put it away, put it away. Sometimes I will tape or pushpin it above my desk, so there is a constant passing flirtation with the poem. But since I am the being with consciousness and agency, I can choose to not walk by, and sometimes, I will do that, too.

I was watching that movie about Stephen Hawking last night, and it occurred to me that I should try to reread A Brief History of Time, though I remember finding it impenetrable when I first bought it. Now I think, if 10 million people bought it, and at least some percentage of that managed to get through it, I should give it another swat. I say this because in my own life, the relation of poetry to time maintains a strong attraction and equal elusivity, and I constantly address the issue of time in my poems. It is the only entity that can give you a completely honest assessment of your work. A friend can’t. A critic can’t. Both may want to be candid, but their own proclivities in large and small terms inhibit that possibility, well-intended or purposeful as it may be. Allowing the poem to brew, to stew in its own juices, invariably calls attention to what demands to be changed. And sometimes, the result it: get rid of me. But keep a few good lines – and those germinate a poem that has not entered that futile realm. I should not even say “futile,” because if that enterprise generated a few good lines, or helped me understand language a little better, then time was not wasted. But the truth is: you have to be willing to “waste time.” Many people think writing poems is a waste of time, anyway. May as well indulge them.

As for the brutality of editing one’s own work – Australian poet Les Murray was the first to say to me: “Sometimes you must kill your darlings.” (Apparently, this quote has many possible sources – Oscar Wilde, Eudora Welty, G.K. Chesterton, Chekhov, and Arthur Quiller-Couch in his Cambridge lectures “On the Art of Writing.”) Whoever said it first – it made sense to me. I recognize that sometimes what I feel is the best line in a poem might be the worst. On the other hand: don’t be a fool. Maybe it is the best, and the rest of the poem needs to step up.

In order to access the cruel inner-editor, I read the poem aloud. I ask it questions – usually when driving, alone. I pretend that I’m interviewing the poem, or (how narcissistic will this sound?) interviewing myself, about this particular poem. On the radio. No one wants to sound like an idiot on the radio, and I’ll usually end up talking to myself about where the poem wants to go and should go, but is not going, and making self-demeaning comments that, fortunately, no one is there to agree with. Then I go home and try to make the poem behave. I love the tension of the editing process. It’s a struggle, a wrestling match, a prize-fight with each poem. I don’t always win, but then, you could say, who is the winner? Is it better if I win or the poem wins? Does the poem want to write itself out of existence? Am I holding on too tight? Ultimately, I am the judge of the poem’s success. The poem cannot say: I’m done. Put a fork in me and send me to The New Yorker.

♦

Meredith: The artist, Juan Gris, said, “You are lost the instant you know what the result will be.” Many would find this counterintuitive, believing it’s actually better to know where you are headed. You?*

PATTY: Poetry distances itself from expository writing by not being goal-oriented. In a piece of persuasive writing, for example, to be effective, clear logic must be in place, and contribute to the result, the summative moment. In contrast, each line of a poem must strive to surprise the reader, while, at the same time, not seem utterly random. One of the many fashions in modern poetry is what Tony Hoagland calls the “skittery poem of our moment.” In a smart essay examining this trend (yes, poetry has trends! It’s just that no one makes any money off of them), he writes, “Systematic development is out; obliquity, fracture, and discontinuity are in.” The skittery poems don’t come naturally to me, but I have written some, particularly when I feel my mind working in perhaps too linear a fashion. Who determines the boundaries of “too”? Me. I love a good narrative poem, and that must move through time with some sense. I don’t want to herald discontinuity to excess, which I see in poems where I feel the writer does not bother to wonder why certain images or moments that seem to have no relation to one another belong near each other in the poem. I think those poems lack rigor, and I think the poet should work hard for the reader’s time and attention.

I never know where a poem is headed when I’m working on it. Never. I do not have a point to make, ax to grind, etc. It’s not that I don’t like points. Did you see that movie, “Planes, Trains and Automobiles”? Steve Martin says to John Candy, a character whose stories never seem to go anywhere: “And another thing: have a point!” I could relate to that. But that’s different than knowing where the poem is going. My poems usually swerve a few times and end up concerning themselves with a completely different issue, or focused on an image or piece of language that I did not see as vital, earlier in the poem’s development.

I grew up in Detroit. I like driving. I like the swerves. And as I get older, I trust the swerves. I used to fear them more – would the poem resume its course? Did the poem need a course? As the poem strays farther and farther from “the interior” (I always think of Joseph Conrad when I use or read that term), and the connection between the initial impulse to write the poem becomes more and more attenuated, it’s easy to get nervous. I think of that Dave Matthews band song that I listen to as I run: “Where are you going?” We are conditioned to desire and maintain direction, and in life, that seems to be, for the most part, how one makes headway. In a poem, it’s the opposite: trusting that there will be a result, but not writing toward that result, and even keeping yourself from knowledge or suspicion of that result. You don’t want to see a light at the end of the tunnel. You want to catch one of those peripheral lights, like the ones in that vision test (that increasingly, I fail. I invent them).

♦

When I asked Patty what she doesn’t usually get to squeeze into a conversation she said: Let’s see: well, I have a strong affection for kitsch, which probably contributes to the “soup” of my poems, but when they enter the realm of cliché, I drop them like the worst old boyfriend. I even had to look up kitsch to explain this: “art, objects or design considered to be in poor taste because of excessive garishness or sentimentality, but sometimes appreciated in an ironic or knowing way.” I am exhausted of the snarkiness of irony, but it remains part of my personality. A good example of kitsch is the lava lamp. I love lava lamps. Some people like them ironically, but I like them genuinely.

One more thing: I am incessantly moved by displays of genuine effort – remember that Olympics commercial in the ‘70s when you see Olga Korbut’s face as she pulls her body, against laws of gravity, up over her head on the balance beam? That made me cry. If I saw it now, I would weep. Finally: I am unmoved by children’s talent shows, though I have children, adore my children, and am fond of talent. I think they should be called “variety shows.” There should be a bar. If I go on more about this, I will sound mean, and I think mean people are tedious, so I’ll stop there. Also: I hate Ron Howard movies.

Photo by Trust “Tru” Katsande on Unsplash