The writer talks about obsession, finishing and a certain something she is completely powerless over. And the art of being one’s own editor.

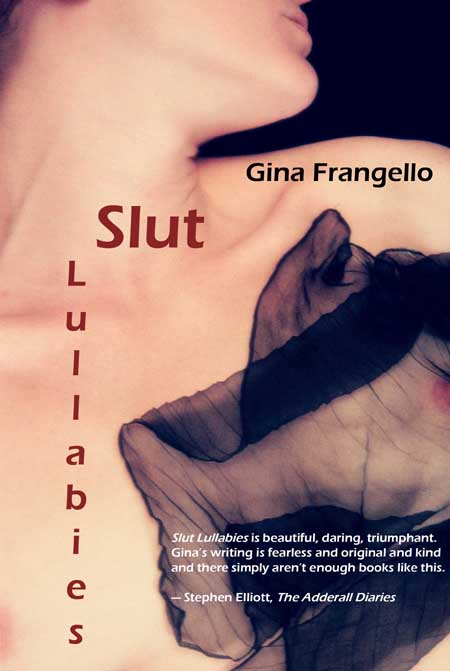

Gina Frangello is the author of the short story collection, Slut Lullabies (a must-read according to Vanity Fair and More) just out from Emergency Press and the novel My Sister’s Continent (Chiasmus 2006.) She is also the Executive Editor of Other Voices Books, an imprint of Dzanc Books, as well as the co-editor of fiction on the popular online literary community, The Nervous Breakdown. Her short fiction has appeared in many journals and anthologies including Five Chapters, StoryQuarterly, Swink, Prairie Schooner and the International Book Award winning A Stranger Among Us: Stories of Cross Cultural Collision and Connection.

MEREDITH: How do you not hold on so tight to a piece of writing that isn’t working (that you wish would work) and let go so you can discover what will work?

GINA: I have a fabulous writing group, and I think both outside feedback and time are key to being able to let go of our own work enough to be able to see it more clearly and approach it from another angle. Giving something to a writing group is helpful not just in terms of getting new perspectives (which are extremely valuable, but can also be conflicting and confusing, as anyone who’s ever been in a workshop knows), but also helpful in that it takes my group time to read my work, and during that necessary downtime I take a break from a story or a novel. I find that as a result of taking some time away, I often can tell pretty clearly which comments from group members resonate with me and just sound “right,” vs. which ones might be interesting but simply don’t fit with me as a writer or with my own vision or intent with a piece. I’ve worked as an editor at Other Voices magazine, Other Voices Books and The Nervous Breakdown for so many years now that I don’t have any illusions about writers always being perfect judges of our own work . . . but I do think we have to maintain a strong sense of our own intent and not just try to turn our work into a “crowd pleaser” by trying to incorporate every change a workshop or writing group member suggests. We have to learn to be our own editor in terms of weeding out what’s useful and what’s not.

MEREDITH: What did you have to unlearn, un-believe about yourself to find your truth as a writer? What had to go?

GINA: I grew up below the poverty line in inner-city Chicago, and although I’ve been writing since before I could actually write (I’d dictate stories to my mom and then illustrate them when I was three or four) and started writing my first “novel” at the age of ten, it never really occurred to me that I could be a writer by profession. I believed this was a luxury reserved for people with trust funds or affluent parents—I had college loans to repay and parents I would need to financially support as they aged. I had majored in psych and gone all the way through a master’s in counseling and was practicing as a therapist when I started writing the manuscript that would become my first novel, My Sister’s Continent, and calling in sick to work all the time, staying up all night to write. I had to look very hard at my life and what I wanted—what would fulfill me. My husband was a struggling academic at that time (a PhD student in space physics, which was a shrinking field) and we didn’t have a lot of financial security, but I ended up realizing that I needed to write and needed to be able to forge a life around that, even if the result looked very different from the financially comfortable life I’d aspired to in my youth.

When you grow up poor, it is very easy to see “making money” as the goal. As I reached adulthood, I realized that one of the huge characteristics of the  working poor tends to be being stuck in menial jobs that are not fulfilling or nurturing—that it’s a larger, more systemic issue than being poorly paid. I was okay, in the end, with being poorly paid if I could make a life I loved. That—more than the income—was the part my parents had never quite been able to achieve and that had haunted them with regrets. Luckily for me, it turned out that my husband found a more conventional career route and has made a nice living, so the existence I’d imagined—on the perpetual edge of poverty—didn’t actually come to pass. But I think realizing I was willing to go there and to give up the rest of it for my writing was essential to being able to take other risks as a writer later on.

working poor tends to be being stuck in menial jobs that are not fulfilling or nurturing—that it’s a larger, more systemic issue than being poorly paid. I was okay, in the end, with being poorly paid if I could make a life I loved. That—more than the income—was the part my parents had never quite been able to achieve and that had haunted them with regrets. Luckily for me, it turned out that my husband found a more conventional career route and has made a nice living, so the existence I’d imagined—on the perpetual edge of poverty—didn’t actually come to pass. But I think realizing I was willing to go there and to give up the rest of it for my writing was essential to being able to take other risks as a writer later on.

MEREDITH: As an author with many projects in motion, many platforms at work and many works in the public eye, how do you balance the left-brain activity of promotion with the right-brain activity of creation? Does it feel like you are moving forward on parallel tracks or is the process more unified and seamless?

GINA: Well, to be honest, it’s really difficult to balance these things . . . not because of left vs. right brain, but simply because of time. I’m a writer, but I’m also many other things, as are most writers. I’ve been an editor for fifteen years, and I teach at two universities, and I blog and write book reviews, so I have to keep all of that going while also promoting my new collection Slut Lullabies, and while trying to create new fiction. But on top of that, of course I have a personal life. I have three children—ten-year-old twins and a four year old—and right now it’s summer and they’re all out of school. As I brought up earlier, I don’t make a lot of money in my line of work, so I try to limit my childcare because I don’t want my work to be a financial liability to my family . . . but on an even deeper level I also don’t want to miss my children’s youth.

One of the great freedoms and luxuries about being a writer and running my own indie press is that I work predominantly out of my home, so even though I put in a lot of hours, I—unlike friends of mine who teach third grade or are attorneys or doctors—have the ability to take my kids to school in the morning, to pick them up, to cook them dinner every night, to take them to the bea ch and the playground in the summer. I’m not going to give that up. Kids grow absurdly quickly and soon enough my husband and I will be alone in our house again, free to work or . . . have sex in the kitchen or whatever . . . whenever we like. So right now, my work has to exist around the rest of my life, the personal part that keeps me energized and nourished and motivated to create. Sometimes the balance isn’t perfect—it’s a constant juggling act, as any working mother can attest.

ch and the playground in the summer. I’m not going to give that up. Kids grow absurdly quickly and soon enough my husband and I will be alone in our house again, free to work or . . . have sex in the kitchen or whatever . . . whenever we like. So right now, my work has to exist around the rest of my life, the personal part that keeps me energized and nourished and motivated to create. Sometimes the balance isn’t perfect—it’s a constant juggling act, as any working mother can attest.

But for me this sometimes means something has to give. Right now, I’m in promotional mode. I’m touring—Austin, New York, Los Angeles, Iowa City, Seattle, Portland—and that’s very difficult with kids. I’m gone for as much as a week at a time, so when I first get home I’m not going to lock myself in my office for ten hours a day writing, I’m going to hang out with them and spend a lot of time talking to them and hugging them and bustling around my kitchen. So I’m not working on a longer writing project right now. I’m doing a lot of publishing industry writing for blogs, especially The Nervous Breakdown, and I just wrote a short story I really like, but many weeks I don’t write. That comes back—it always comes back. I’ve learned not to have anxiety about that, because the drive to write is something that always returns in me, and when it does I’m pretty much powerless to stop it, so I’ve learned to enjoy my downtime.

MEREDITH: Writing—or the dream of calling oneself an author or writer—seems, for many, to have this highly addictive, seductiveness about it. Like: I’d really be someone if I could write. Or be a writer, author, etc. But it’s not writing that imbues itself with these characteristics, it’s the person. Why, do you think, it’s such a seductive slope? Have you ever been seduced?

GINA: This is such a funny question to me because, while I know you’re right and I see this mentality a lot in my writing students, I spent most of my early life trying not to be a writer and thinking being a writer would bring me to some kind of derelict financial ruin, so it’s hard for me to grasp why people think it’s going to be so glamorous! Other than janitors, I don’t know a whole lot of professions less glamorous than being a writer. You spend a lot of time in your pajamas, alone in front of a computer. You spend a lot, lot of time being rejected, and even when your work is accepted you’re usually radically underpaid, and your audience is usually very small. Most of us are never going to be Hemingway . . . or J.K. Rowling. Vanity Fair is not going to do a fancy little spread on us like they did on Donna Tartt in the 1990s! I mean, Slut Lullabies got one little blurb in Vanity Fair’s June issue and I nearly went into coronary arrest I was so happy . . . the writer’s life is one that is solitary and often desperate for small scraps of recognition. You fail a lot. You may be very poor. Your relatives and non-writer friends don’t understand what you do, and don’t understand why you’re not famous, and assume it means you’re either lazy or untalented . . .

And yet, of course, there are incredibly seductive aspects to being a writer. If you’re doing it right, your characters are incredibly seductive. The ability to live multiple lives is seductive. Touring, even on a low budget, can make you feel slightly like a rock star, even if maybe a D-list rock star. Editing and writing can help you meet a lot of extremely interesting people. I love this life and the lifestyle, but I think a lot of young people are under vast misperceptions about it. It’s not about drinking scotch during the day and waiting for fame to arrive. In fact, the more you expect it to be some kind of cliché like that, the less you probably care about writing and the more you care about image. In this culture, having a good “image” has a lot to do with making money, so there are a hell of a lot of more suitable professions to people with that goal than writing fiction, that’s for sure.

MEREDITH: I’ve asked the question before: What does beginning feel like? Look like? But I’d like to flip that and ask: What does finishing look like? As in a particular work? Is it harder than starting? Is there a part of you that doesn’t want to let go?

GINA: I’ve talked about this issue before in some other interviews—it’s a very pertinent question for me. I have a very difficult time letting go of longer work—of novels—that take years to create and where I’ve been living with the characters for a prolonged period of time. Stories aren’t like that for me, because when I’m writing I binge-write and I usually finish a story in a couple of days. But I work slowly on novels—I have long periods where I may not be writing but where the characters are always with me, or when I’m revising as I go along. I may spend four years on a novel, maybe more. I’ve had a few . . . I guess you could call them “psychological disturbances” . . . on letting a novel go. I can get manic when I’m approaching that end stage. It’s delicious and terrifying, and afterwards there’s a big crash. Longer works are risky, on a variety of levels. I love them for that. I also choose them carefully, because of the risk involved. They have to choose me—it has to be a true obsession.

I’ve been writing my whole life, but I’m still learning that the grief—the loss—after an obsession like that is always temporary. I always think I’ll never love another character or another project that way again, but that’s the crazy beauty of writing fiction . . . there is always another love, another obsession down the line.

Gina (who I interviewed here for my “Agents and Editor” series) teaches at Columbia College Chicago, Northwestern University’s School of Continuing Studies, and has contributed book reviews and journalism to The Huffington Post, the Chicago Tribune and the Chicago Reader. Check her out online at her website, (and in real life with three kids on her body or in front of her computer answering emails).

According to popular opinion, she never sleeps.

[Thanks (again) Gina!]

First published June 2010.